Salman Toor’s rising star – revolutionary art in Pakistani diaspora

October 19, 2021

Cover photo credit: Time 100 Next 2021

By: Alexandra Bregman

Two years ago, hardly anyone outside of Pakistan had heard of Salman Toor. Born in Lahore, Pakistan in 1983, his moody figures were quietly collected by the elites of his home country, pondered by the Brooklyn set, and shopped around by the New York staple for South Asian art, Aicon Gallery. With the November 2020 ‘How Will I Know’, his first solo show at the Whitney Museum in New York City, however, Toor completely exploded onto the global art scene and became an overnight art world darling.

The prices speak for themselves. In December 2020, Toor’s first-ever auctioned painting, Rooftop Ghost Party I (2015), sold for eight times its estimate at Christie’s for $822,000. Weeks later at Phillips in London, Liberty Porcelain (2012) sold for nine times its estimate of £40,000, at £378,000 ($505,688). And by June 2021, Toor broke his own sales record of $867,000 when Girl with Driver (2013) sold for $890,000 in Hong Kong.

The 15-painting retrospective at the Whitney Museum drew its title from a painting called Dancing to Whitney (2018). It was one of Toor’s first artworks in what has since become his signature style, based on a memory of dancing to Whitney Houston with friends. In the painting, and in life, the sinewy queer male figures were pondering the lyrics. How will they know what the future holds?

The present holds The Frick Collection. Living Histories: Queer Views and Old Masters at the Frick Madison space features Toor with three other New York artists, all focused on queer identity, in conversation with European art: Doron Langberg, Jenna Gribbon, and Toyin Ojih Odutola, on view through January 2022.

Among the reasons Toor did not initially capture the attention of museums and collectors was that he was afraid. The artist spent the first 14 years of his life growing up in Lahore, where he told BOMB magazine he was deemed a “sissy boy”, “often bullied at school and policed everywhere else.” In an interview with Them magazine, Toor said shame was used as a weapon and the threat of violence was always underneath the surface.

In a later conversation with fellow artist Chitra Ganesh for the Whitney showcase, Toor added, “When I grew up in a largely gendered and homophobic culture, I was very used to safe spaces, so the paintings move in between private and public spaces…I realized I was still creating safe spaces, because they made me feel happy and comfortable. And the more I had, the more abundantly I felt at home…”

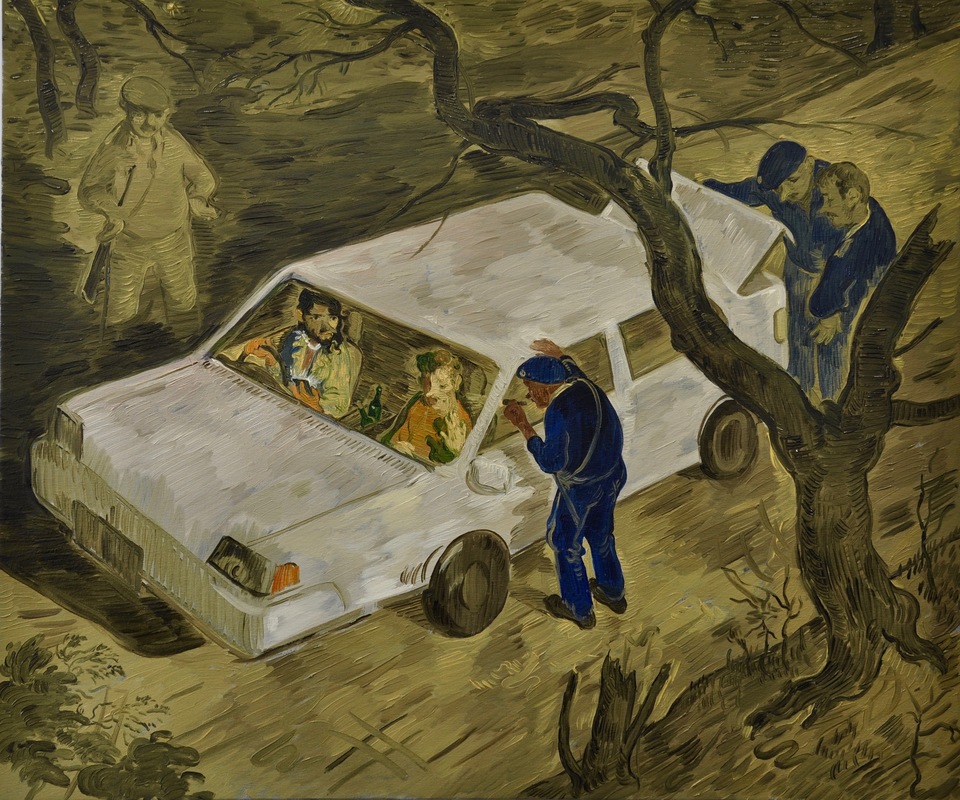

Paintings like The Smokers (2018) and Nightmare and Car Boys (2019) reference the terror of lurking officers in a state defined by its strict penal code, a far cry from the joyfulness so clearly shown in scenes from New York. This spilled over into his art, which catered to South Asian audiences. The work that is now so beloved was just for his apartment, a private world where he could be free.

The new works quickly went viral on Instagram. The groups of figures resonated with audiences during the pandemic, who were hungering to reconvene and socialize, and speak to a rapidly changing collective consciousness. As societal norms are questioned on an international scale, the question remains how this will circle back into Pakistan.

“I was very lucky to be part of a culture that was changing here,” Toor told Whitney curator Ambika Trasi, “In which people were being assertive, wanting to be seen, producing new ideas of beauty and multi-ethnic progressiveness that are imminently exportable.”

Aligned with the “queer intelligentsia,” Black Lives Matter and the feminist art of friend Indian artist, Ganesh, some of Toor’s work shows scenes of brown men in contemporary nightlife settings in New York. As a Pakistani artist, his work expresses apolitical expressions of joy that are at odds with a global perception that associates Pakistan with terrorism, security, the Taliban and religious extremism.

Rather, Toor’s happiest paintings are scenes of the interior home and underground bar scene in New York and Pakistan alike, where he could—finally—feel safe. The intimacies of everything from apartment trinkets to technology and skin creams reveal the hodgepodge of the everyday, a take on 21st century portraiture thus far not yet fully represented.

Toor’s work is a part of an important canon of contemporary South Asian artists who draw inspiration from colonial Indian miniature painting (including Shahzia Sikander), but it is particularly poignant because it finds the self where it has never been before.

In art history class at college in Ohio, the only dark-skinned subjects of Old Master paintings were the servants. Now, he belongs in a powerful canon with Ganesh’s open sexuality and goddess Kali, Black artist Kerry James Marshall’s scenes of familiarity. There are queer artists like Israeli painter, Doron Langberg, and even David Antonio Cruz with his Puerto Rican Pieta (2006). To the Pakistani gaze, this untraditional crew is a reminder that radical acceptance is happening across the pond, and that neglecting to do so will bleed out top talent.

Perhaps in reaction to the neglect of this rich inner world, Toor’s subjects take on a mythic, even melodic quality. Dance is a recurring theme in Toor’s work, which stems both from Baroque paintings and a brief stint on a hippie commune, but also evokes the festivities depicted in subcontinental miniature painting, particularly the ragamalas.

Toor’s training was initially highly derivative, drawing inspiration from Dutch and Italian Old Masters and the flourish of Mughal women’s eyes and shoes. The paintings still possess a slightly French Post-Impressionist movement; Toor says he drew inspiration for the mix-and-match palette of the figures from Picasso, but the bedroom scenes and bright backgrounds suggest Henri Toulouse-Lautrec or Amedeo Modigliani. In any case, the global perspective of the artist threads together the many images he has consumed throughout his life, seeking his own power through nostalgia.

The paintings, Toor told BOMB, are much about dichotomy: the Old Master versus the Instagram photo, overconnected but not interconnected, the Old Master light of a cell phone. Loneliness in the public eye, happiness and freedom punctuated by the passions of queer life.

But in this fantasy universe, the hairy brown bodies always find themselves at peace. They possess a mythic power; Toor imagines them as creative and educated, challenging societal norms about race and foreignness in America. They may never belong in the traditional sense as South Asians in diaspora, but they belong fully unto themselves.

Alexandra Bregman is a freelance writer with a specialization in art and art markets. She has previously written about South Asian art for The Art Newspaper, The Asian Art Newspaper, and Nikkei Asia among other publications.