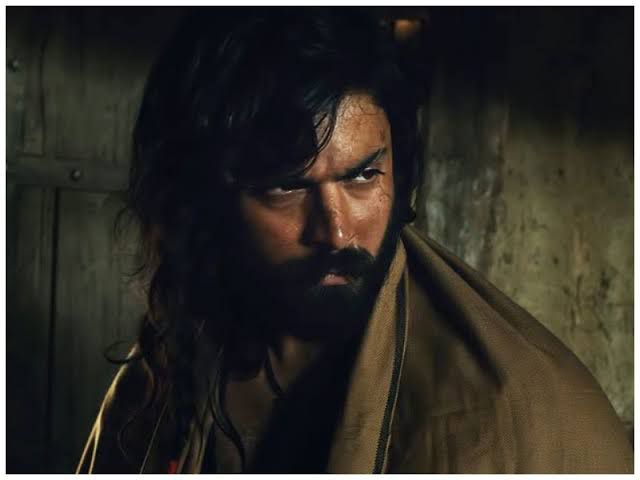

Cover photo credit: The Legend Of Maula Jatt movie poster (Geo films)

By: Ushah Kazi

Spoiler alert; this report does not contain major spoilers for The Legend Of Maula Jatt, but it does spoil the ending for Maula Jatt (1979) and Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi’s short story Gandasa.

Even before its release, Bilal Lashari’s latest offering kept Pakistani cinegoers and culture buffs on the edge of their seats, for years. The first look trailer of The Legend Of Maula Jatt, released in late 2018, became an instant classic. But initial whispers about the Waar director turning his attention to what he himself called “Pakistan’s original film genre” had been making rounds since 2013.

The saga of Lashari’s potential ‘magnum opus’ thus dates back nearly a decade. But the story of Maula Jatt, and his unique brand of cinema goes back further still. Not only can the 1979 film be called one of the most popular Pakistani films of all time, but there have been several attempts at remaking it. In 2013, while interviewing Lashari about his rendition, The Express Tribune reported that they had been approached by four production houses in two years, regarding potential Maula Jatt reboots.

It is interesting then, that in order to breathe new life into the story, Bilal Lashari has had to detach it from the context that made the original a cult classic in the first place.

The Actual Legend Of Maula Jatt

The character of Maula was first introduced via Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi’s short story titled Gandasa.

While it has been credited by the screenwriter of both the original and 2022 reboot as his inspiration, there are notable differences. In fact, Qasmi’s story, according to Ali Kapadia, is not only dissimilar to what was seen in the 1970’s films (fun fact, Maula Jatt itself was a sequel to Wehshi Jatt) but was almost antithetical. Literary Maula, according to Kapadia, serves as a cautionary tale about toxic masculinity and how the revenge-driven culture of the time was shaping Pakistani men (the story was published against the 1960s backdrop of war and nationalistic calls to enlist).

Throughout the story, Maula is opposed to violence, but must resort to it because of the emasculating insistence of his mother. By the end, he can’t avenge his family as per her decree, and instead lets his foe walk away, bursting into tears in the aftermath. When his mother lambasts him, Maula asks, “can’t I even cry?”

Kapadia asserts, “with that picture of a tearful eye, Gandasa is Qasmi’s response to “boys don’t cry” – the nation’s reassuring lie.”

Maula’s Film Debut

By the time Qasmi’s story was reimagined for the screen, Pakistani cinema itself had gone through a transformation.

According to Sher Khan and Hashim Bin Rashid, an oft forgotten legislation that shaped Punjabi cinema in particular, was the Goonda Act (passed in 1959 and enforced in 1968). Reportedly while it was in force, “over a dozen men” were labeled as ‘goondas’ (a person engaged in a list of activities deemed illicit) and killed in police encounters across Punjab.

They claim that as a response, families of these men ventured into film production, in a bid to tell their side of the story. Many of the films that fall into the ‘gandasa’ genre (so named because of the ax that Maula wields in every iteration of the story) were produced by them.

By the 1970s, there was also a constant threat of censorship (even Maula Jatt wasn’t cleared by the Censor Board, but was able to draw in the crowds because of the Lahore High Court’s stay order on the ban). Simultaneously, the aftermath of the 1971 war, meant that Urdu language film distributors lost a chunk of their audience.

Such a landscape was ripe for the introduction of a genre that reflected the chaos of the time. And thus, Sultan Rahi’s turn as the film version of Maula became a sensation. As Khan and Rashid note, not only did Rahi present a kind of hero never seen before, but the stories of such films, which borrowed heavily from the caste identities across the region, struck a chord with audiences.

Kapadia explains the difference between Maula’s origins and his foray into films like this, “in essence, the film ‘fixes’ Maula into what a son ought to be – an instrument of war.” Considering the context that produced the films, this is perhaps unsurprising.

Maula Jatt 2022

The trajectory of Pakistani cinema has been incredibly unstable. It hasn’t gone through peaks and troughs; it has experienced multiple deaths and attempted rebirths. There have been decades of slow growth, followed by complete stagnation. Because of this, much of the current audience is not aware of the country’s most iconic films. Even Fawad Khan, who stars as the titular character, admitted that he had limited exposure to the original prior to being approached for the remake.

What has survived however, is an animosity towards the gandasa film genre. Bilal Lashari himself explained these sentiments when he said that such films “are blamed for the death of Lollywood”.

Such accusations are a little unfair, when as noted by Anwar Maqsood in a rare interview with the man himself, Sultan Rahi was for all intents and purposes a one-man-institution. Nor do such dismissals acknowledge the potential of the genre. To quote Lashari, “the entire world has been exporting their own styles and versions of cinema outside their territory, but we have been silent”.

However, it’s interesting to note that despite his interest in the local classic, Bilal Lashari’s rendition has international leanings. Deviations in the storyline notwithstanding, this is perhaps the biggest change that the filmmakers decided on. The original source materials were cemented in the culture of the land. Yet here, the choices seem to borrow from international media.

Calling the director “Pakistan’s only master of action,” Rafay Mahmood and Zeeshan Ahmad acknowledge that he “opts for certain set and prop elements that stick out. Anglo-Saxon wood barrels and tables inside a mud structure doubling as a pub… In an ideal world perhaps, the makers of TLoMJ (The Legend Of Maula Jatt) could have played more with local visual elements…”

Reviewing the film for Something Haute, Hassan Chaudhry notes that while audiences are informed that the story takes place in Punjab, the exact location of the village is not revealed.

In his review for The Guardian, Cath Clarke called it “Game of Thrones meets Gladiator”. In light of its penchant for hypermasculinity, Mahmood and Ahmad also compared it to KGF. Perhaps its aesthetics can also be compared to recent Sanjay Leela Bhansali historicals, and later seasons of Dirilis: Ertugrul.

Moreover, Sarwar Bhatti, the producer of the original (who had previously been embroiled in copyright suits with the producers of the reboot) stated that “after watching the trailer, I felt that these characters belong to some barbarian kingdom.

Arguably, this international focus is anything but coincidental. Lashari has maintained that several aspects of the original needed to be updated to appeal to modern audiences. And if box office numbers are accounted for, the international appeal has worked in the film’s favor. As of the writing of this report, The Legend of Maula Jatt has collected Rs. 19 crore, from five countries in three days. There is every indication that it will continue to break ground.

Ushah Kazi has written for a number of Pakistani and Canadian publications. She has also published a book about Pakistani cinema titled, The Pop-Culture Junkie’s Guide to Pakistani Cinema, which is available on Amazon.