Cover photo credit: Canva

By: Sarah Munir

Suggested reading time: 8 minutes

Earlier this month, the Pakistan Cricket Board announced a refreshing new parental support policy that would allow both men and women cricketers some time off after having a child. As part of the new set of policies, women cricketers will be allowed to take a year-long paid maternity leave, in addition to the option of switching to a non-playing role as they approach their maternity leave, Dawn News reported. A contract for the following year will also be guaranteed when leaving for maternity leave. When the athletes return to work, they will be provided physical training and support to rehabilitate after childbirth. Male cricketers are also allowed concessions, and will be able to take a month-long paid paternity leave. On May 16, Pakistan cricket team captain Bismah Maroof announced her decision to take an indefinite maternity leave.

The policy reform by PCB has been widely lauded as a much-needed step forward in providing childcare support and fostering gender diversity in the workplace.

Tell me more …

Though women constitute 49 percent of Pakistan’s population, female labor force participation stands at 22 percent – placing it among the lowest in South Asia and the world. The gender gap stands at 23.7 percent with only 4.2 percent women holding senior or middle management positions. According to the Global Gender Gap Index Report 2020, published by the World Economic Forum, Pakistan also ranks 151 out of the 153 countries, surpassing only Iraq and Yemen.

Despite maternity protection being labeled a fundamental labour right by major human rights treaties like UDHR, ICESR and CEDAW, Pakistan has failed to provide sufficient childcare facilities to its workers, especially women. As a result, most women drop out of the workforce as they near or experience childbirth, reducing their economic participation drastically. When half of the country’s labor force remains unsupported and watches from the sidelines, it is no surprise that the economic performance takes a massive hit.

Between a rock and a hard place

According to local law, employers are expected to provide 12 weeks of paid maternity leave (16 weeks in Sindh), free healthcare during and after pregnancy, protection from dismissals and periodic nursing breaks in accordance with the International Labor Organization’s Maternity Protection Convention 1919 (No 3). But the measures fall short of what is required or needed.

And in some cases, it directly affects the mothers who are trying to build a career while caring for their families. Kiran*, a medical officer at a Karachi-based private healthcare facility describes her employer’s policy of granting only a 45-day unpaid leave after delivery as “exhausting.” “Not having a daycare facility at the workplace also exacerbates the guilt of not being with my newborn. It feels like I am losing on both ends,” she shares.

Women who are employed in the private sector usually have better luck if the organization is progressive, the labor force is unionized and/or if their immediate supervisors are cooperative. Madiha Javed Qureshi, who was working at Nestle at the time of her pregnancy lauds the company for being extremely flexible with their maternity and paternity leave policies and providing day care services to parents. “Being a first-time mother is an extremely difficult and anxiety-ridden period for working women,” she says. “If my employer had not extended the kind of support they did, I can’t imagine how I would have continued working.”

According to Iftikhar Ahmed, founder of Center for Labor Research, paying for maternity leave and establishing day care centers should not be the employer’s responsibility. Instead, he recommends building of day care centers at a community level by the government and financing maternity leaves by social security rather than making it an employer liability.

Care and support goes a long way

Even when maternity/paternity leaves are flexible, lack of affordable and reliable childcare facilities often discourages young mothers from returning to work. With more and more families becoming nuclear, most women start contemplating leaving work during pregnancy as there is no one to care for the child. Zainab Bhatti, who works in a managerial role at LUMS, gives credit to the institution for allowing her a generous maternity leave but wishes there were more options for bringing your children to the workplace. “I am a special needs mother and it is difficult for me to leave my baby for prolonged hours.” Her concern is echoed by Bisma*, whose decision to continue work was impacted by the availability of a subsidized day care facility at the private hospital she worked at. “I don’t think I would have been able to work full-time without this support,” she says.

Unfortunately, if these needs are not met, legal recourse for workers is limited. Even in cases of unfair dismissals or discriminatory policies by employers, there isn’t much employees can do, says Parvez Rahim, a labour law and employee relations expert. “The labour litigation process in Pakistan is expensive and time consuming. Even the cases of ‘alleged unfair dismissals from service’ take years for decisions,” he said. Hence, young parents are not left with much choice besides relying on each other or families for support or dishing out money from their own pockets to ensure that their child is in the safe hands of a private caretaker.

Is change on the horizon?

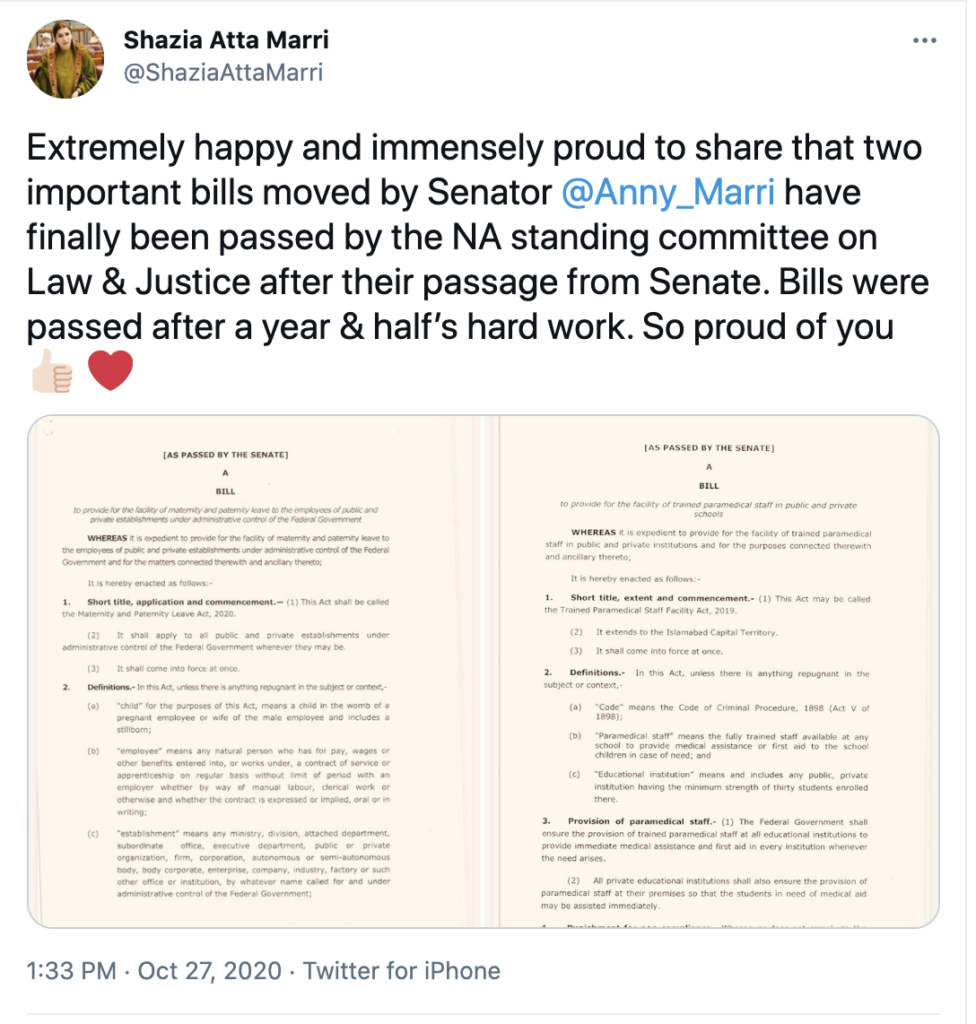

In January 2020, the Senate passed the Maternity and Paternity Leave Bill, 2018, which entitles women to a maternity leave of six months and also allows men a paternity leave of three months. Mothers and fathers may get further three- and one-month optional leaves but those will be unpaid, it says. The employer won’t be allowed to terminate the services of an employee for seeking leave under the provisions of the bill. The bill was moved by Pakistan Peoples Party Senator Quratulain Marri and is still to be considered by the National Assembly.

While some have lauded the bill for providing relief to working mothers and paving a path for equality, where men and women share the role of providing for and raising children together, others have reservations due to its limited application. The bill will be applicable only to enterprises within the administrative control of the federal government. Moreover, experts think some checks and balances are also required to ensure it is not misused as a recreational leave but instead allows fathers to step up as the primary caretaker while allowing mothers to rest or return to work.

Given the physical and financial strain of having a child, coupled with a lack of support from the state and employers, more and more young parents are choosing to delay childbirth. Those that don’t are often forced to take a sabbatical from work and/or forgo their career completely. According to Rahim, the sphere of labour laws in Pakistan is in “complete shambles” after the passage of the 18th Amendment in April 2010, which devolved more control to the provinces. There is little focus on maternity leave and working women’s rights when other critical labour welfare laws applicable to the entire workforce are on the “verge of total collapse”, he added. But some young parents choose to remain hopeful for change. “Women can be mothers and have ambitious careers at the same time. The world is making it happen for us, it’s about time that Pakistan takes a step in that direction too,” Kiran says as she gets ready for her first-born.

A look at the rest of the world

Here are some countries that are miles ahead in terms of extending support to both parents:

Finland: Starting in 2021, each parent will be allowed 164 days, or about seven months. A single parent can take the amount of two parents, or 328 days.

Denmark: New moms in Denmark get a total of 18 weeks of maternity leave: four weeks before the birth and 14 weeks after, at full pay. During the 14-week period, the father can also take two consecutive weeks off.

Sweden: New parents in Sweden are entitled to 480 days of leave at 80% of their normal pay.

Norway: Mothers can take 49 weeks at full pay or 59 weeks at 80% pay, and fathers can take between zero and 10 weeks depending on their wives’ income.

New Zealand: Earlier this year New Zealand began to offer a three-day paid bereavement leave for couples who have suffered a miscarriage. India and China also have similar policies in place that allows couples to take time off and grieve in case of experiencing a misscarriage.

Some names have been changed due to privacy concerns

Sarah Munir is a digital journalist with a focus on the intersection of technology and media. She has worked with several publications including Dawn, Facebook, Forbes, and most recently Twitter. You can reach her @SarahMunir1.